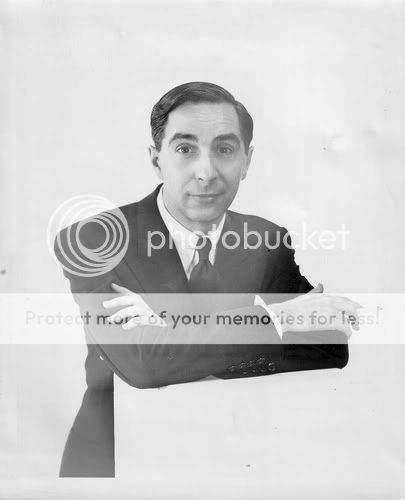

Born: Norman David Levinson in Noblesville, Indiana, 20 April 1900. Education: Studied illustration at Parsons School of Design, New York, 1919; fashion design at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, 1920-22. Career: Costume designer, Paramount Pictures, Long Island, New York, 1922-23; theatrical costume designer, 1924-28; designer, Hattie Carnegie, New York, 1928-40; partner/designer, Traina-Norell company, New York, 1941-60; director, Norman Norell, New York, 1960-72. Exhibitions: Norman Norell retrospective, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1972. Awards: Neiman Marcus award, Dallas, Texas, 1942; Coty American Fashion Critics award, 1943, 1951, 1956, 1958, 1966; Parsons medal for distinguished achievement, 1956; Sunday Times International Fashion award, London, 1963; City of New York Bronze Medallion, 1972. Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts, Pratt Institute, 1962. Died: 25 October 1972, in New York.

Simple, well-made clothes that would last and remain fashionable for many years became the hallmark of Norman Norell, the first American designer to win the respect of Parisian couturiers. He gained a reputation for flattering design while Traina, whose well-heeled clientéle appreciated the snob appeal of pared-down day clothes and dramatic eveningwear. From his early years with Hattie Carnegie, Norell learned all about meticulous cut, fit, and quality fabrics. Regular trips to Paris exposed him to the standards of couture that made French clothes the epitome of high fashion. Norell had the unique ability to translate the characteristics of couture into American ready-to-wear. He did inspect each model garment individually, carefully, in the tradition of a couturier, and was just as demanding in proper fabrication and finish. The prices of "Norells," especially after he went into business on his own, easily rivaled those of Paris creations, but they were worth it. The clothes lasted, and their classicism made them timeless.

Certain characteristics of Norell's designs were developed early on and remained constant throughout his career. Wool jersey shirtwaist dresses with demure bowed collars were a radical departure from splashy floral daydresses of the 1940s. World War II restrictions on yardages and materials coincided with Norell's penchant for spare silhouettes, echoing his favorite period, the 1920s. Long before Paris was promoting the chemise in the 1950s, Norell was offering short, straight, low-waisted shapes during the war years. For evening, Norell looked to the flashy glamor of his days designing costumes for vaudeville.

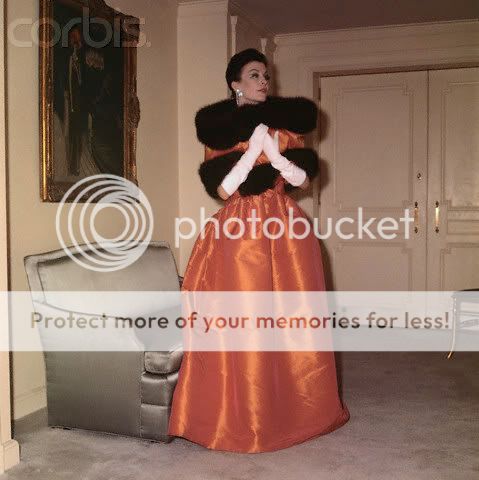

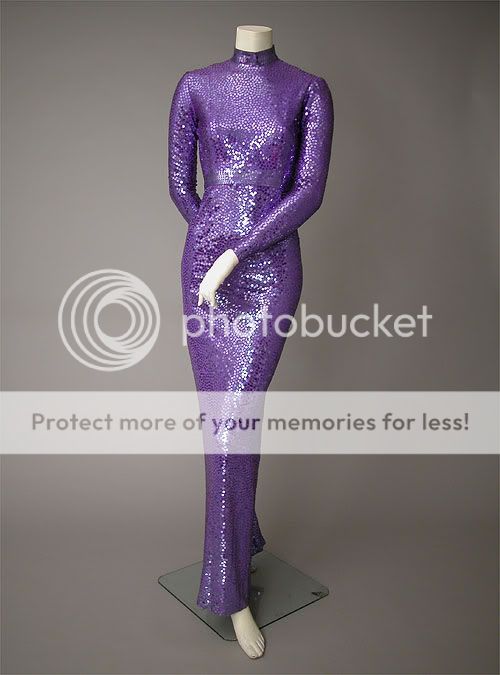

Glittering paillettes, which were not rationed, would be splashed on evening skirts—paired with sweater tops for comfort in unheated rooms—or on coats. Later, the lavish use of all-out glamor sequins evolved into Norell's signature shimmering "mermaid" evening dresses, formfitting, round-necked and short-sleeved. The round neckline, plain instead of the then-popular draped, became one of the features of Norell's designs of which he was most proud. "I hope I have helped women dress more simply," was his goal. He used revealing bathing suit necklines for evening as well, with sable trim or jeweled buttons for contrast. Variations on these themes continued throughout the years, even after trousersuits became a regular part of Norell's repertoire.

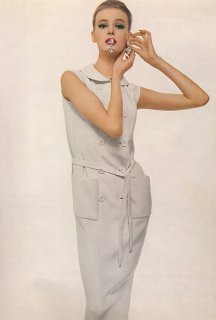

Striking in their simplicity, Norell suits would skim the body, making the wearer the focus of attention rather than the clothes. Daytime drama came from bold, clear colors such as red, black, beige, bright orange, or pale blue, punctuated by large, plain contrasting buttons. Stripes, dots, and checks were the only patterns, although Norell was credited with introducing leopard prints in the 1940s, again, years before they became widespread in use. Norell's faithful clients hailed his clothes as some of the most comfortable they had ever worn.

Early exposure to men's clothing in Norell's father's haberdashery business no doubt led to the adaptation of the menswear practicality. An outstanding example was the sleeveless jacket over a bowed blouse and slim woolen skirt, developed after Norell became aware of the comfort of his own sleeveless vest worn for work. As in men's clothing, pockets and buttons were always functional. Norell created a sensation with the culotte-skirted wool flannel day suit with which he launched his own independent label in 1960. His sophisticated clientéle welcomed the ease of movement allowed by this daring design. As the 1960s progressed Norell presented another masculine-influenced garment, the jumpsuit, but in soft or luxurious fabrics for evening. Just as durability and excellent workmanship were integral to the best menswear, so they were to Norell's. Men's dress was traditionally slow to change; Norell stayed with his same basic designs, continually refining them over the years. He developed the idea that there should be only one center of interest in an outfit, and designed only what he liked.

What he liked was frequently copied, both domestically and overseas. The short, flippy, gored, ice skating skirt was copied by Paris. Aware of piracy in the fashion business, Norell offered working sketches of the culotte suit free of charge to the trade to ensure that at least his design would be copied correctly. This integrity earned him a place as the foremost American designer of his time. Unlike most ready-to-wear that would be altered at the last moment for ease of manufacture, no changes were allowed after Norell had approved a garment. His impeccable taste was evident not only in the clothes, but in his simple life: meals at Schrafft's and Hamburger Heaven, quiet evenings at home, sketching in his modern duplex apartment, and unpublicized daily visits to assist fashion design students at Parsons School of Design.

As the designer whose reputation gained new respect for the Seventh Avenue garment industry, Norell was the first designer to receive the Coty Award, and the first to be elected to the Coty Award Hall of Fame. True to his innate integrity, he attempted to return his third Winnie award when he learned that judging was done without judges having actually seen designers' collections. Norell promoted American fashion as founder and president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, but also by giving fledgling milliners their start in his black-tie, special event fashion shows. Halston and Adolfo designed hats for Norell, for, as in couture, Norell insisted upon unity of costume to include accessories.

As the "Dean of American Fashion," Norell was the first to have his name on a dress label, and the first to produce a successful American fragrance, Norell, with a designer name. Some of his clothes can be seen in the films, such as The Sainted Devil, That Touch of Mink and The Wheeler Dealers. Show business personalities and social leaders throughout the country treasured their "Norells" for years.

—Therese Duzinkiewicz Baker