Scotsman.com (I looked for the books on fashion thread but could not find it )

I enjoyed this article and would love to read the book.

The way we wore

BY JESSICA KIDDLE

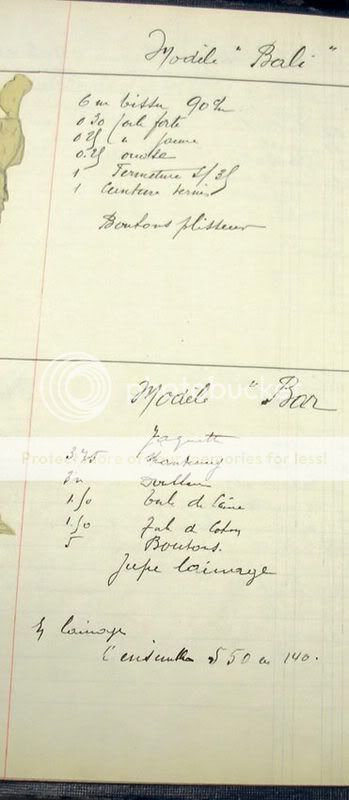

WHEN SUMMING UP THE MAGIC of a custom-made dress, Christian Dior once wrote: "Couture is the marriage of design and material. There are many instances of perfect harmony - and there are few of disaster."

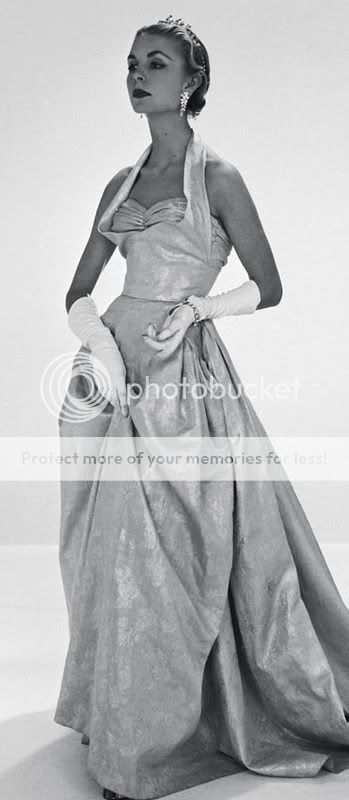

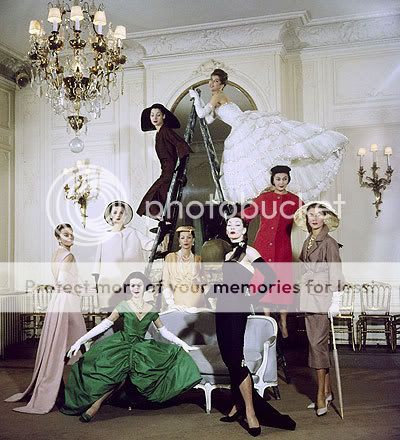

Instances of such harmonious perfection were never more frequent than in the 1950s. The couturiers Cristóbal Balenciaga, Hubert de Givenchy and Coco Chanel were also setting the showrooms of Paris's Champs-Élysées alight at the time of Dior's meteoric rise to fame, and fashion was at its most glamorous and luxurious.

As a result, the decade from 1947 to 1957 (during which Dior set up shop in Paris, dictated the popular style of the day and spearheaded the resurgence of fashion after the Second World War) is regarded as a golden era for haute couture. It was a time when the world held its breath awaiting the latest creations from Paris, and when the notion of the supermodel took hold. Thanks to advances in print and photography, the theatre of fashion began to be played out to a wider audience in glossy magazines such as Vogue.

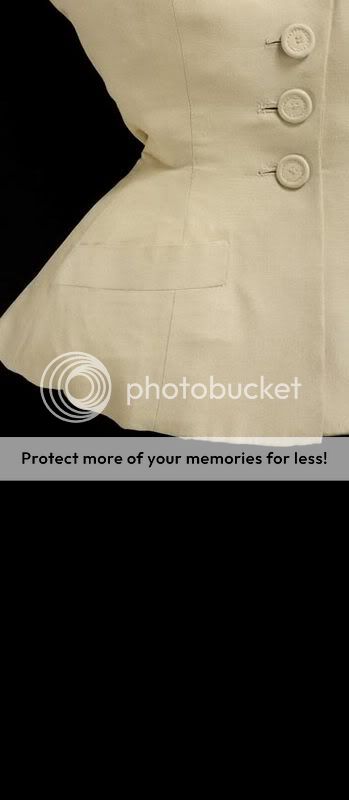

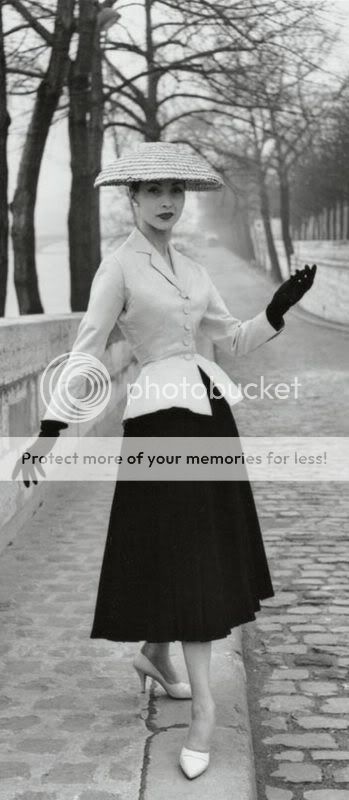

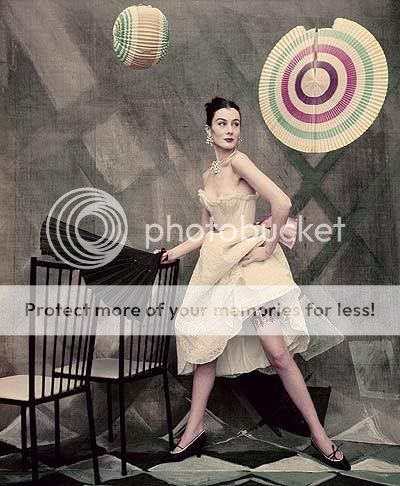

A new book celebrates this special era in fashion history and marks the 60th anniversary of the launch of Dior's New Look - the cinched-in waist, full skirt and large bust that became the signature shape of that time. The Golden Age of Couture - Paris and London, 1947-1957 has been written to accompany an exhibition of the same name which opens at London's Victoria & Albert Museum next week.

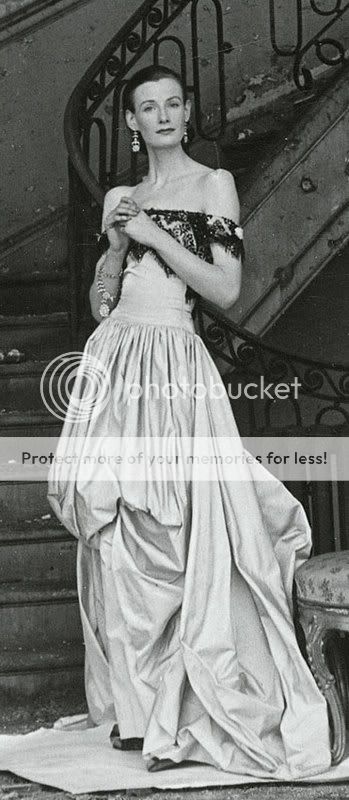

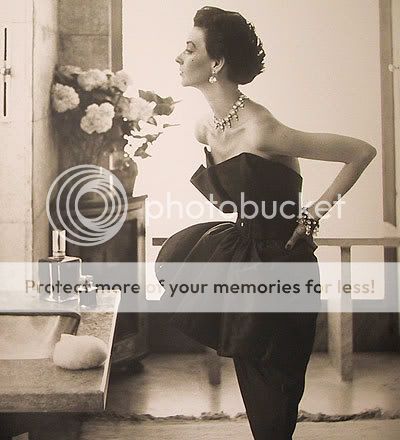

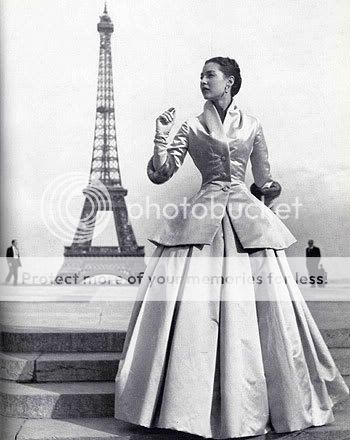

Featuring photographs of some of the most iconic designs of that age, including a black and white shot of Dior house model Renée posing in front of the Eiffel tower wearing the two-piece creation Zemire (Dior named all his designs) as well as an image of model Dovima posing with two elephants in an evening dress designed by Yves Saint Laurent, the book offers an insight into a moment and style which, although long since passed, is now more in evidence than ever thanks to the retrospective trends on the high street.

As Claire Wilcox, senior curator of 20th century and contemporary fashion at the V&A, and editor of the book, explains, the reason the clothes of this decade are so special is because their frivolous bustles and bows were set against the contrasting backdrop of a rubble-filled Europe in recovery from the war.

"Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the launch of the New Look, which used copious amounts of fabric, was an antidote to the thrift of the war years," says Wilcox. "The look was also very nostalgic, referencing pre-war fashion and evoking a sense of the prosperity which was in complete contrast to the militaristic fashion of the early 1940s.

"While a good number of houses had survived the war, Dior was regarded as the saviour of haute couture. His romantic vision created a mood of optimism after the gloom of the previous few years, while the complex artistry of his gowns drew on skills unique to Parisian couture, providing employment for numerous atelier supervisors and seamstresses."

Haute couture - which literally means "high sewing" - was synonymous with Paris long before the war, however. It was brought to the city by English-born couturier Charles Worth, who opened what is regarded as the world's first haute couture fashion house in 1858, the House of Worth, and who quickly realised that, for couture to flourish, its exclusivity and quality would have to be maintained at all costs. In 1868 he founded the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, which regulated and monitored the growing number of couture houses.

Yet while he was instrumental in establishing Paris as the capital of fashion, it is the postwar period that jumps out of the pages of fashion history, for two reasons. First, it is memorable for Dior's unashamed use of colour, fabric, fur and embellishment (which he lavished on creations made for the likes of Grace Kelly and Vivien Leigh).

Not that couture began and ended with Dior. Houses such as Balenciaga, Jacques Fath and Pierre Balmain all rose to fame during that time. As a result, anyone of social standing in mainland Europe and the UK as well as America, South America and the Far East would put aside three weeks of each season to visit the couture houses (with their lavish boutiques and mazes of workshops) for fittings.

High-ranking socialites and royalty always looked to Paris when it came to dressing for a special occasion. With an eye for fashion, some women even secured their ticket into the upper echelons of society with the right dress, while the majority would make do with more affordable copies and, thanks to licensing, either the perfume or the lipstick.

"Couture is an elitist form of design which relies on the best fabrics, trims and workmanship from great artisans all working in concert," says 1950s fashion expert and author Alexandra Palmer, who contributed to the book. "The leading socialites and celebrities would all dress at the leading houses: Marlene Dietrich at Dior, for example, and of course Audrey Hepburn at Givenchy. But private clients were mature women who were dressed as such. It was about making a statement of correctness and taste and the right label did that."

The second reason this decade is so special is that it bore witness to the development of the complex business model that saw Dior become the most successful fashion name of the 20th century through advertising, licensing, perfume and publicity. Described as "a strange mixture of theatre and commerce, showmanship and business" by British-born Ginette Spanier, directrice of couture at Balmain, it was this model born out of a couturier's ability to sell designs to commercial buyers and manufacturers (who would make more affordable versions) on both sides of the Atlantic that saw the fashion houses develop into empires and grow into the household names of today.

It was, as Wilcox puts it, also to be a "late flowering just before the end". Dior died suddenly of a heart attack in 1957, by which point couture was in decline thanks to the accessibility of ready-to-wear.

But just as they had kept going without pins or fabric throughout the war, the proudly anachronistic fashion houses survive today, though there are only a few left and private clients now number in the low hundreds (which is not surprising, considering an embellished couture dress would cost in the region of £200,000).

But while the future of couture can now legitimately be called into question, the importance of its legacy cannot.

"The influence this era had on fashion is enormous," says Palmer. "1950s couture is still the source for many contemporary designs and the interest in wearing an authentic vintage couture design means that the clothes of that era are still a means of acquiring individualism in the face of mass marketing."

Wilcox agrees: "The legacy of Dior's 'golden age' is manifold. The rarefied skill of couture in the postwar years set a standard for dressmaking that has never been surpassed. Postwar couture is indelibly associated with the New Look, a style that influenced popular design in a way that was unprecedented in fashion history and, 60 years on, its memory still has great potency."

• The Golden Age of Couture: Paris and London 1947-1957 is at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, from 22 September to 6 January 2008. Tel: 0870 906 3883, or visit www.vam.ac.uk

• The Golden Age of Couture edited by Claire Wilcox is published by V&A Publications, priced £35.

This article: http://living.scotsman.com/index.

I enjoyed this article and would love to read the book.

The way we wore

BY JESSICA KIDDLE

WHEN SUMMING UP THE MAGIC of a custom-made dress, Christian Dior once wrote: "Couture is the marriage of design and material. There are many instances of perfect harmony - and there are few of disaster."

Instances of such harmonious perfection were never more frequent than in the 1950s. The couturiers Cristóbal Balenciaga, Hubert de Givenchy and Coco Chanel were also setting the showrooms of Paris's Champs-Élysées alight at the time of Dior's meteoric rise to fame, and fashion was at its most glamorous and luxurious.

As a result, the decade from 1947 to 1957 (during which Dior set up shop in Paris, dictated the popular style of the day and spearheaded the resurgence of fashion after the Second World War) is regarded as a golden era for haute couture. It was a time when the world held its breath awaiting the latest creations from Paris, and when the notion of the supermodel took hold. Thanks to advances in print and photography, the theatre of fashion began to be played out to a wider audience in glossy magazines such as Vogue.

A new book celebrates this special era in fashion history and marks the 60th anniversary of the launch of Dior's New Look - the cinched-in waist, full skirt and large bust that became the signature shape of that time. The Golden Age of Couture - Paris and London, 1947-1957 has been written to accompany an exhibition of the same name which opens at London's Victoria & Albert Museum next week.

Featuring photographs of some of the most iconic designs of that age, including a black and white shot of Dior house model Renée posing in front of the Eiffel tower wearing the two-piece creation Zemire (Dior named all his designs) as well as an image of model Dovima posing with two elephants in an evening dress designed by Yves Saint Laurent, the book offers an insight into a moment and style which, although long since passed, is now more in evidence than ever thanks to the retrospective trends on the high street.

As Claire Wilcox, senior curator of 20th century and contemporary fashion at the V&A, and editor of the book, explains, the reason the clothes of this decade are so special is because their frivolous bustles and bows were set against the contrasting backdrop of a rubble-filled Europe in recovery from the war.

"Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the launch of the New Look, which used copious amounts of fabric, was an antidote to the thrift of the war years," says Wilcox. "The look was also very nostalgic, referencing pre-war fashion and evoking a sense of the prosperity which was in complete contrast to the militaristic fashion of the early 1940s.

"While a good number of houses had survived the war, Dior was regarded as the saviour of haute couture. His romantic vision created a mood of optimism after the gloom of the previous few years, while the complex artistry of his gowns drew on skills unique to Parisian couture, providing employment for numerous atelier supervisors and seamstresses."

Haute couture - which literally means "high sewing" - was synonymous with Paris long before the war, however. It was brought to the city by English-born couturier Charles Worth, who opened what is regarded as the world's first haute couture fashion house in 1858, the House of Worth, and who quickly realised that, for couture to flourish, its exclusivity and quality would have to be maintained at all costs. In 1868 he founded the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, which regulated and monitored the growing number of couture houses.

Yet while he was instrumental in establishing Paris as the capital of fashion, it is the postwar period that jumps out of the pages of fashion history, for two reasons. First, it is memorable for Dior's unashamed use of colour, fabric, fur and embellishment (which he lavished on creations made for the likes of Grace Kelly and Vivien Leigh).

Not that couture began and ended with Dior. Houses such as Balenciaga, Jacques Fath and Pierre Balmain all rose to fame during that time. As a result, anyone of social standing in mainland Europe and the UK as well as America, South America and the Far East would put aside three weeks of each season to visit the couture houses (with their lavish boutiques and mazes of workshops) for fittings.

High-ranking socialites and royalty always looked to Paris when it came to dressing for a special occasion. With an eye for fashion, some women even secured their ticket into the upper echelons of society with the right dress, while the majority would make do with more affordable copies and, thanks to licensing, either the perfume or the lipstick.

"Couture is an elitist form of design which relies on the best fabrics, trims and workmanship from great artisans all working in concert," says 1950s fashion expert and author Alexandra Palmer, who contributed to the book. "The leading socialites and celebrities would all dress at the leading houses: Marlene Dietrich at Dior, for example, and of course Audrey Hepburn at Givenchy. But private clients were mature women who were dressed as such. It was about making a statement of correctness and taste and the right label did that."

The second reason this decade is so special is that it bore witness to the development of the complex business model that saw Dior become the most successful fashion name of the 20th century through advertising, licensing, perfume and publicity. Described as "a strange mixture of theatre and commerce, showmanship and business" by British-born Ginette Spanier, directrice of couture at Balmain, it was this model born out of a couturier's ability to sell designs to commercial buyers and manufacturers (who would make more affordable versions) on both sides of the Atlantic that saw the fashion houses develop into empires and grow into the household names of today.

It was, as Wilcox puts it, also to be a "late flowering just before the end". Dior died suddenly of a heart attack in 1957, by which point couture was in decline thanks to the accessibility of ready-to-wear.

But just as they had kept going without pins or fabric throughout the war, the proudly anachronistic fashion houses survive today, though there are only a few left and private clients now number in the low hundreds (which is not surprising, considering an embellished couture dress would cost in the region of £200,000).

But while the future of couture can now legitimately be called into question, the importance of its legacy cannot.

"The influence this era had on fashion is enormous," says Palmer. "1950s couture is still the source for many contemporary designs and the interest in wearing an authentic vintage couture design means that the clothes of that era are still a means of acquiring individualism in the face of mass marketing."

Wilcox agrees: "The legacy of Dior's 'golden age' is manifold. The rarefied skill of couture in the postwar years set a standard for dressmaking that has never been surpassed. Postwar couture is indelibly associated with the New Look, a style that influenced popular design in a way that was unprecedented in fashion history and, 60 years on, its memory still has great potency."

• The Golden Age of Couture: Paris and London 1947-1957 is at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, from 22 September to 6 January 2008. Tel: 0870 906 3883, or visit www.vam.ac.uk

• The Golden Age of Couture edited by Claire Wilcox is published by V&A Publications, priced £35.

This article: http://living.scotsman.com/index.

Last edited by a moderator:

)

)