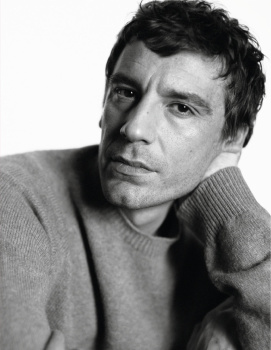

style.comLVMH Prize finalist. Creative director of Paco Rabanne. Founder of the fledgling label Atto. French designer Julien Dossena is juggling a lot of roles this spring, but he was in New York last week wearing his Paco Rabanne hat. Dossena replaced Manish Arora at Rabanne early last year shortly after leaving Balenciaga, where he worked under Nicolas Ghesquière. By his own account, he has his work cut out for him at Rabanne. Outside of France and fashion circles, the brand is known for little more than perfume and men’s cologne, despite the late designer’s groundbreaking designs of the 1960s. Jane Fonda wouldn’t have been half as convincing as Barbarella without her Rabanne chain mail, and photos of pretty young things in his metal shifts encapsulate the futurism and free love of the era. But the company has floundered in recent years. “The image of the brand before was a bit blurry,” Dossena said. “Now we are taking back the reins.” Over lunch with Style.com, the designer talked Jane Birkin, Françoise Hardy, and why chain mail will always be essential. —Nicole Phelps

How did Paco Rabanne sales go for Fall?We got opinion-leader kind of shops: Corso Como, Maria Luisa, The Webster, Blake, Just One Eye, Dover Street Market in New York and London. It’s a good start. And Barneys for the bags.

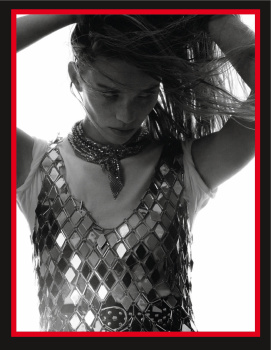

Did any piece in particular connect with buyers?We really wanted to emphasize a daywear wardrobe, but—there’s always a but—the stores need a bit of chain mail on the rack. People love it, they buy it. The challenge is to figure out how we can integrate chain mail into a daywear wardrobe.

As you say, the vision of the brand was blurry before. How do you intend to clear it up?

If women have only one Paco Rabanne dress in their closets, the brand isn’t going to develop. So we want to move away from the super-embroidered dresses that were the base of Rabanne before. We want to make it a classic brand for a younger customer. This season, we got the stores we need to deliver that commercial message. Now we’re working on our first pre-collection. We’re going to open our first shop in about a year and a half. Those are the first steps to having a strong brand.

Where will the shop be?

In Paris. Paco Rabanne is a classic from the sixties like Courrèges or Cardin. It can compete now with Balmain, Carven, those kinds of names. Paco Rabanne can be one of them. In France, Paco Rabanne is really deep in the culture. People love the name in France. I don’t know about America.

People who know fashion here know Jane Birkin and Françoise Hardy in the dresses—those cool metal dresses.

That’s what we want to bring back, that coolness that we love from those images. The question is how to translate those images into new product. If there’s a main word that we’re trying to do, it’s effortless.

To be a successful revival brand these days, you can’t just be about the past, right?

It has to be a balance of not losing the signature, but not being impressed by it, either—not being controlled by it. In five, six, seven years, Paco could become a lifestyle brand. Like if you travel, what kind of clothes do you want to wear? If you go to the countryside on the weekend, what do you want to take? I’m super-interested in that aspect and bringing that together with the visual futuristic signature of Paco Rabanne. It’s a good challenge. The good thing, I hope, is that we cleaned the image of the brand quite fast. And now we can move forward.

No one was paying much attention to the label, but very quickly you seem to have caught people’s attention.

I hope. The name deserves it.

Do you think launching your own brand, Atto, at the same time as you signed on at Paco Rabanne has been helpful?

Yes. You learn so much on your own. When you launch your own brand, you have to be super-logical. Basically, it’s either you can do that or you can’t. That’s all. It teaches you not to be afraid to say, “OK, we can’t make a show? Don’t make a show.” But also to find the power in not making a show by really focusing on your products.

That’s what I wanted to do after I left Balenciaga. At Balenciaga I was working on the shows, and when you design clothes for a show it’s totally different than when you design for a customer. Paco Rabanne has taught me that a good basic with a little something more can be super-interesting. Each look has to go on a woman, has to be relevant.

But is it hard to manage two brands?

I just started wondering about that now. It happened randomly that I started Atto and Paco at the same time. I launched Atto in December [2012] just after Balenciaga. Then Paco called me for freelance in mid-January. Now that we’re adding pre-collection in Paco, I wonder what is the best way to keep the balance. At the end, the signature is me. Of course I have the Paco name to hold on to, but in the end, it’s what I think is good.

How is the Paco girl different from the Atto girl?

She’s different, but she’s still my girl. Maybe at Paco she’s more sensual, she’s more rich. At Atto, her look is more sharp, more clean.

Are you going to stick to showing Atto by appointment only during the pre-collections?

Yes, I don’t want it to go too fast or too big. I really want to take my time and enjoy it. To not put pressure on me or the collection. What I’d love to do is co-branding, or collaborations with people who have a specific technique or savoir faire, like Atto Mackintosh, Atto and Charvet shirts. That’s a dream. I love the Comme des Garçons model—you know the way they do those jackets with Barbour. I love that. They keep the essence of Barbour, but they add all their craziness and twists to it.

I’m almost afraid to do a show for Atto because I worry that I will lose the aim of Atto. Doing a show totally transforms your vision of your clothes. It makes you think about the casting, all these kinds of things. When I design Atto now, I say, “OK, is the girl going to be comfortable in that dress? What can she mix it with?” I’m afraid to lose that mix-and-match, modular feeling of Atto.

What about the LVMH award? You’re one of the twelve finalists, for Atto. Congratulations.

I was super-honored and super-happy. You know, in France, there is not much support for young designers and young brands. It’s really hopeful when you see that a big group like LVMH is looking at what young designers are doing. It’s a good thing. It means you are not playing anymore. It’s serious. If Atto doesn’t win, we already won, just to be part of the designer group. It’s quite an eclectic group of finalists. And I’m so happy it’s going on in Paris, you know, finally.

There is something moving. My friends and I are super-happy that J.W. Anderson is coming to Loewe, that Nicolas Ghesquière is coming to Vuitton. You can feel a good energy now in Paris.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Julien Dossena - Designer, Creative Director of Paco Rabanne

- Thread starter Flashbang

- Start date

wmagazine.comJulien Dossena

This up-and-coming designer is en route to fashion stardom.

When Julien Dossena quit his job as a designer at Balenciaga in December 2012, after the departure of his boss, Nicolas Ghesquière, panic soon set in. “There was no point in staying on,” he admits. “But I’d worked there for four years, often 24/7, and it felt sad.”

- March 24, 2014 9:00 AM | by Alice Rawsthorn

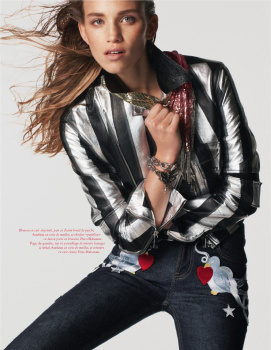

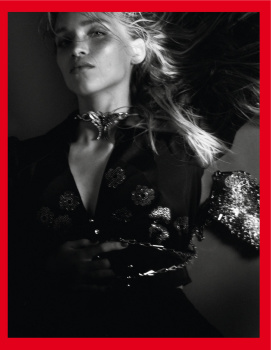

- Photography by Emma Summerton

Styled by Elodie David Touboul

Not that he felt that way for long. Just a few weeks later, the boyishly handsome 31-year-old was offered a consultancy at Paco Rabanne. The house’s owner, the Puig group, was struggling to revive Paco Rabanne’s allure as a futuristic label that had dazzled the fashion scene in the 1960s alongside Courrèges and Pierre Cardin. Having gone through two chief designers in as many years, CEO Marc Puig offered the creative director role to Dossena just eight months after he’d joined the company. Dossena’s first collection of glossy leather dresses, metal mesh tops, and silver jeans was widely praised when it was unveiled in Paris last autumn. “I’ve always loved Paco Rabanne for its rebelliousness and modernity,” Dossena enthuses. “I want the new collections to have the same aesthetic impact, but for the young women of now.”

It is worth remembering just how radical Paco Rabanne, now 80 and retired, was. He got his start in 1966 with the collection 12 Unwearable Dresses in Contemporary Materials, in which he used metal, plastic, rubber, and cardboard. He continued to experiment with paper, knitted-fur, and fiberglass clothes for, among others, the singer Françoise Hardy and the actress Brigitte Bardot. Well known for his spiritual beliefs, Rabanne fled Paris shortly before August 11, 1999, convinced that on that day the Russian space station Mir would fall on the city and obliterate it.

Dossena himself is partial to futuristic visions, albeit as a sci-fi enthusiast who enjoys J.G. Ballard’s novels rather than as a prophet of doom. He was born in Brittany, studied art history in Paris, and then fashion in Brussels. After graduating, in 2008, he was hired by Ghesquière, who is now his boyfriend. Participating in Balenciaga’s technical experiments was ideal preparation for Paco Rabanne, which shares a similar laboratorial culture: For his debut, Dossena worked with some of the original Paco Rabanne fabric suppliers, but he took advantage of the latest technologies. “Chain mail was Paco Rabanne’s signature,” observes Laure Heriard Dubreuil, who ordered the collection for her Miami store, the Webster. “But Julien designed the pieces to look lightweight and effortless.”

Rejuvenating the clothes is only the start for Dossena, who also runs Atto, a label he cofounded with two fellow Balenciaga alums. Like Ghesquière and other designers he admires—including Martin Margiela and Helmut Lang—he sees the collection as part of a wider vision. “If you begin with the clothes and add the bags, the logo, the boutiques, and everything else, then you can go like a cannonball!” he says. “What I love about sci-fi is that you get to invent a whole world, complete with landscape, architecture, and characters. Paco Rabanne did that with his women in metal dresses surrounded by metal walls and metal furniture. Now it’s up to me to build my own visual reality.”

- Hair by Marion Anée for Leonor Greyl at airportagency.com; makeup by Aude Gill at Studio 57. Models: Lena Hardt at DNA Model Management; Harleth Kuusik at the Society Management; Mijo Mihaljcic at IMG Models; Maja Salamon at Next Management. Digital technician: Nick Dehadray; photography assistants: Edward Singleton, Paul Jedwab; fashion assistant: Florie Vitse; production: Belinda Foord at Shiny Projects.

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,531

- Reaction score

- 20,538

Time to invest in sturdier bookracks, Julien!

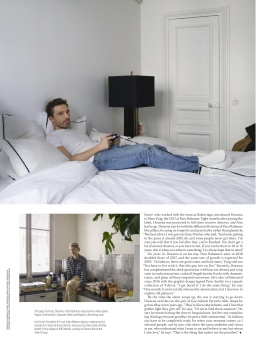

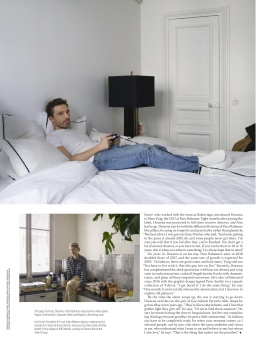

W Magazine Vol #3 2019

Mix Master

Photographer: Nigel Shafran

Stylist: Sara Moonves

Hair: Kei Terada

Makeup: Emi Kaneko

Manicure: Alex Falba

Cast: Julien Dossena, Emmy Rappe. Jean-Philippe Chemin, Kelela, Marina Fois, Angie Rubini, DJ Benoit Heitz

Photographed in his Paris apartment.

W Magazine Digital Edition

W Magazine Vol #3 2019

Mix Master

Photographer: Nigel Shafran

Stylist: Sara Moonves

Hair: Kei Terada

Makeup: Emi Kaneko

Manicure: Alex Falba

Cast: Julien Dossena, Emmy Rappe. Jean-Philippe Chemin, Kelela, Marina Fois, Angie Rubini, DJ Benoit Heitz

Photographed in his Paris apartment.

W Magazine Digital Edition

Last edited:

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,531

- Reaction score

- 20,538

Shop Design and Displays

Paco Rabanne under Julien Dossena - Paris:

Of all the details that jostle for attention within the new Paco Rabanne retail space, the floor might just be the winner. Shortly after stepping off Rue Cambon, you feel a surface more forgiving than pavement; next, you notice the triangular tiling and claylike hue; then you wonder, Could it be . . . leather? Indeed, says artistic director Julien Dossena on a walk-through prior to the boutique’s opening. It’s a bold choice—one wonders how it will age—yet it speaks to how the brand was built on Paco Rabanne’s material fearlessness and reinforces a concept that defies cookie-cutter.

This is the first realization of a stand-alone retail space under Dossena’s direction; not since 2002 has Paco Rabanne existed as a boutique. In a way, this allowed Dossena more latitude, since he wouldn’t be forced to break radically or make a smooth transition. But as it quite literally lays the groundwork for a new access point into the brand—not to mention a template for future locations—the vision needed to be equally focused and adaptable.

Hence the “toolbox” idea, which is reflected in the modular functioning, allover aluminum paneling customized with enlarged perforated motifs like enlarged locker doors, and displays that can be adjusted to reveal and conceal. Hanging bars drop down and corrugated metal vents flip up, food truck style. The lighting, while direct, feels unthreatening. The effect, even amid the industrial aesthetic, feels intimate.

“A boutique is actually a very pure expression of the brand,” says Dossena, who had never previously worked on retail design. He enlisted Belgian architects Kersten Geers and David Van Severen for the project, and points out how the paneling establishes a space within the space—especially since it is offset from the usual right-angle alignment. This, he says, reaffirms a “human scale” within an early 1930s architectural setting that loosely borrows from Adolf Loos. “There’s an aspect that’s super radical but also accessible,” he explains.

If these are the touches that people may perceive subconsciously, others are more evident: Dossena reached out to master perfumer Dominique Ropion (Frédéric Malle’s Portrait of a Lady and Vetiver Extraordinaire, among others) to conceive a subtle ambient scent. Electronic music DJ Benoit Heitz, aka Surkin, mixed together abstract sounds rather than a conventional playlist.

The store isn’t Paco Rabanne’s only sign of expansion; a new website developed by the Wednesday agency includes e-commerce in Europe and links to Barneys New York for North America and Farfetch globally. All of this is supported by a refreshed visual identity care of the Zak Group and the brand’s first campaign, a series of sleek, uninhabited rooms photographed by Maurice Scheltens and Liesbeth Abbenes.

But its new home at 12 Rue Cambon resonates on a personal level for Dossena, who says his Paris pals were always asking where they could find his designs. (They remain available at Maria Luisa within Printemps.) And the good news for those in other fashion capitals: Dossena confirms that this store is just the beginning.

Vogue

Paco Rabanne under Julien Dossena - Paris:

Of all the details that jostle for attention within the new Paco Rabanne retail space, the floor might just be the winner. Shortly after stepping off Rue Cambon, you feel a surface more forgiving than pavement; next, you notice the triangular tiling and claylike hue; then you wonder, Could it be . . . leather? Indeed, says artistic director Julien Dossena on a walk-through prior to the boutique’s opening. It’s a bold choice—one wonders how it will age—yet it speaks to how the brand was built on Paco Rabanne’s material fearlessness and reinforces a concept that defies cookie-cutter.

This is the first realization of a stand-alone retail space under Dossena’s direction; not since 2002 has Paco Rabanne existed as a boutique. In a way, this allowed Dossena more latitude, since he wouldn’t be forced to break radically or make a smooth transition. But as it quite literally lays the groundwork for a new access point into the brand—not to mention a template for future locations—the vision needed to be equally focused and adaptable.

Hence the “toolbox” idea, which is reflected in the modular functioning, allover aluminum paneling customized with enlarged perforated motifs like enlarged locker doors, and displays that can be adjusted to reveal and conceal. Hanging bars drop down and corrugated metal vents flip up, food truck style. The lighting, while direct, feels unthreatening. The effect, even amid the industrial aesthetic, feels intimate.

“A boutique is actually a very pure expression of the brand,” says Dossena, who had never previously worked on retail design. He enlisted Belgian architects Kersten Geers and David Van Severen for the project, and points out how the paneling establishes a space within the space—especially since it is offset from the usual right-angle alignment. This, he says, reaffirms a “human scale” within an early 1930s architectural setting that loosely borrows from Adolf Loos. “There’s an aspect that’s super radical but also accessible,” he explains.

If these are the touches that people may perceive subconsciously, others are more evident: Dossena reached out to master perfumer Dominique Ropion (Frédéric Malle’s Portrait of a Lady and Vetiver Extraordinaire, among others) to conceive a subtle ambient scent. Electronic music DJ Benoit Heitz, aka Surkin, mixed together abstract sounds rather than a conventional playlist.

The store isn’t Paco Rabanne’s only sign of expansion; a new website developed by the Wednesday agency includes e-commerce in Europe and links to Barneys New York for North America and Farfetch globally. All of this is supported by a refreshed visual identity care of the Zak Group and the brand’s first campaign, a series of sleek, uninhabited rooms photographed by Maurice Scheltens and Liesbeth Abbenes.

But its new home at 12 Rue Cambon resonates on a personal level for Dossena, who says his Paris pals were always asking where they could find his designs. (They remain available at Maria Luisa within Printemps.) And the good news for those in other fashion capitals: Dossena confirms that this store is just the beginning.

Vogue

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,531

- Reaction score

- 20,538

Phuel

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2010

- Messages

- 5,466

- Reaction score

- 7,645

He reminds me of Reservoir Dog-era Tim Roth with the new Caeser-cut (although the furrowed-brow thing is a tad too serious: It’s just fashion, Julien…). But you know, no matter how they try to hustle his designs, it’s just not working. The whole chainmail thing was done to perfection by Gianni already, with the armour-plating thing already done so well by Christopher Bailey at Burberry Prorsum and Karl at Chanel. This all feels and looks so reductive when it’s his main calling card. And LOL @the heart imprints that turn the whole dress into a cheapo Victoria’s Secret giftcard box.

Lola701

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 27, 2014

- Messages

- 10,298

- Reaction score

- 19,577

What they have done (MAS and him) with Paco Rabanne is a tour de force for me! The fact that the brand has a fashion credibility nowadays is beyond miraculous!

Paco Rabanne is real good RTW at a decent price, nothing more, nothing less. Does it have emotion or that thing that makes it exceptional or A THING in fashion? No! But it’s good to have this kind of proposition that doesn’t rely on « luxury »!

They have the best boots anyway!

Paco Rabanne is real good RTW at a decent price, nothing more, nothing less. Does it have emotion or that thing that makes it exceptional or A THING in fashion? No! But it’s good to have this kind of proposition that doesn’t rely on « luxury »!

They have the best boots anyway!

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,535

- Reaction score

- 4,722

I hate not speaking French fluently, it takes me forever to read an article. Thanks for sharing tho.

He seems like a very sweet guy from an interview I saw a while ago, so it seems weird that he tries to look so serious for his portrait.

He seems like a very sweet guy from an interview I saw a while ago, so it seems weird that he tries to look so serious for his portrait.

LadyJunon

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 11, 2021

- Messages

- 3,124

- Reaction score

- 5,706

Julien Dossena could possibly be next at Jean Paul Gaultier:

Source: WWDJulien Dossena Eyed as Next Guest Couturier at Jean Paul Gaultier: Sources

He is creative director at Paco Rabanne, which is also owned by Spanish group Puig.

By MILES SOCHA

MARCH 3, 2023, 1:00AM

Could Jean Paul Gaultier’s next guest couturier be recruited from within the Puig fashion family?

According to sources, Paco Rabanne creative director Julien Dossena is in discussions to design a one-off haute couture collection for Jean Paul Gaultier. Both Paris-based fashion houses are owned by the Spanish group Puig.

Gaultier sat front row at Dossena’s fall 2023 fashion show for Paco Rabanne on Wednesday. Gaultier demurred when asked if his presence might signal his choice, noting that he attended primarily to pay respects to the founding couturier, who died last month at age 88.

Contacted by WWD, Gaultier and Puig officials declined all comment on Thursday.

Should Dossena be selected, his collection for Jean Paul Gaultier would be unveiled during the next couture week in Paris, which runs from July 3 to 6.

At the creative helm of Rabanne since 2013, Dossena is prized for his meticulous, yet zesty designs with a futuristic sheen.

A graduate of La Cambre in Brussels, Dossena won the 1.2.3 prize at the International Festival of Fashion and Photography in Hyères in 2006. From 2008 to 2012, he was a senior designer in the Balenciaga studio, working closely with former creative director Nicolas Ghesquière.

Haider Ackermann, Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, Glenn Martens of Y/Project and Diesel, and Chitose Abe of Sacai were the first four talents invited to guest-design a Gaultier couture collection following the founder’s retirement from the runway in 2020.

It’s quickly become a highlight of couture week — and fueled interest in Gaultier’s vast and eclectic oeuvre, achieved over a career spanning 50 years.

The idea of different designers interpreting one couture brand first came to Gaultier in the ’90s when one Paris house “found itself without a designer,” according to Gaultier, who has never named names, though the house in question is believed to be Jean Patou, famously ignited by Christian Lacroix in the ’80s. (Gaultier also worked at Patou earlier in his career.)

Spain’s Puig, while known primarily for its fragrance forte, has been ramping up activities with the fashion houses it owns, which in addition to Paco Rabanne and Jean Paul Gaultier include Nina Ricci, Carolina Herrera and Dries Van Noten.

Its owned fragrance brands include Byredo, Penhaligon’s and L’Artisan Parfumeur. It also operates Charlotte Tilbury and has a derma division.

LadyJunon

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 11, 2021

- Messages

- 3,124

- Reaction score

- 5,706

Source: WWDEXCLUSIVE: Paco Rabanne Is Revving Up With Makeup, More Boutiques

The Puig-owned house is pursuing a strategy of brand elevation and feminization under the new Rabanne banner.

By MILES SOCHA, JENNIFER WEIL

JUNE 28, 2023, 1:02AM

PARIS — Paco Rabanne is ready for its close-up, and global expansion on multiple fronts, having synced up its fashion and fragrance businesses.

Abbreviating its name to simply Rabanne, the Puig-owned fashion and fragrance house is launching makeup, kicking off a d-to-c intensification with a flagship boutique in New York City — and slowly applying its new visual identity to various product lines and retail spaces.

Disclosing a host of changes and initiatives exclusively to WWD, Puig beauty and fashion president José Manuel Albesa also reported strong business momentum at Paris-based Rabanne, which has been logging 40 percent growth in recent years — and is poised to soon cross the 1 billion euro revenue threshold.

“There’s been an elevation of the brand, and a feminization of the brand. It’s been a lot of work these last five years,” he said in an interview.

And it’s all coming together in 2023, by all accounts a big year for Rabanne with a now-unified image between fashion and fragrance dubbed One Rabanne. Crystalizing this is the new logo for the entire brand, with typeface inspired by the brand’s 1968 hit perfume Calandre, a monogram that is being trickled into textile patterns, accessories and fragrances.

“The brand is having a moment that is incredible,” Albesa enthused.

It’ll reach a zenith during Paris Fashion Week in September, when Rabanne unveils its spring 2024 collection on the runway with expanded ranges of eveningwear, denim and knitwear — and the Avenue Montaigne flagship will bear the new lower-case Rabanne banner.

By that time, the playful new Rabanne makeup, with 90 stock keeping units housed in gleaming silver-colored tubes and compacts, will have landed on the brand’s e-commerce site and counters in Selfridges in the U.K. and Sephora in Europe, with Ulta in the U.S. coming on stream Oct. 1.

Albesa made clear the crucial contribution of designer Julien Dossena, who has revved up Rabanne’s fashion credibility, reworked and clarified the brand’s key aesthetic codes, and recently made important inroads with celebrities by adding more eveningwear.

For example, when Beyoncé stepped onto the stage at the Stade de France last month, she wore a gleaming, waist-cinched Rabanne gown assembled from round, mirror-effect plates.

Dossena arrived as creative director of the fashion house 10 years ago, and he’s been locked in to lead Rabanne’s next chapter.

Albesa would not comment directly on the French designer’s contract, but it is understood that it was recently renewed, which should squelch recurring speculation Dossena might soon defect to another fashion house.

“There is nothing to announce. Julien is here to stay,” Albesa said with a laugh and a big smile. “And he’s more excited than ever to explore new themes, and he’s more energetic than ever.”

“The brand has such an iconic and immediately recognizable legacy; it’s a unique and strong vision we carry on,” Dossena said. “We try our best to honor the values of the founder: freedom and empowerment.”

WWD broke the news on March 3 that Dossena would become the latest guest designer to realize a one-off haute couture collection for Jean Paul Gaultier, also owned by Puig.

The show is scheduled for July 5 during Paris Couture Week, and Albesa hinted that Dossena would blend Rabanne references with Gaultier’s vast and eclectic oeuvre, achieved over a career spanning 50 years.

Another high-profile project is in view: a holiday collaboration with Swedish fashion giant H&M. WWD also broke the news of that project on Feb. 22, though officials at both companies remain mum about the tie-up.

Dossena burst onto the fashion radar in 2006, when he won a prize at the International Festival of Fashion and Photography in Hyères. He went on to spend four years as a senior designer at Balenciaga, working under then-creative director Nicolas Ghesquière, who instilled in him an exacting, forward-looking approach to design.

Dossena joined Paco Rabanne, famed for its Space Age designs, in early 2013 under then-creative director Lydia Maurer, and in parallel launched his own label, Atto, which he put on hold to concentrate on Paco Rabanne when he was promoted to creative director later that year.

Albesa said the designer, then 30 years old, instantly won the approval of the fashion press, fond of his meticulous yet zesty designs with a futuristic sheen.

“Julien has this capacity to continue innovating,” Albesa said. “While remaining consistent and very loyal to the brand codes, he’s able to — every single time — bring something new, and how this is now being infused into accessories, into jewelry, into beauty, into makeup is incredible.”

Calling Dossena “instrumental in creating the house,” Albesa characterized him as “more than a fashion designer. He has a vision for the brand.”

Among the key codes of the brand that now appear across fashion, accessories and beauty products are metal mesh, silver and gold in combination, square chain links, and round and hole-punched metallic discs like the ones the founder hammered into “12 Unwearable Dresses” back in 1966, cementing Rabanne’s fame.

Albesa grabbed a clicker to show on a large monitor a rendering of a future Rabanne makeup stand. Incorporating marble amid the gleaming silver and gold. The unit includes large images of Rabanne jewelry, fashions and handbags, portraying the aesthetic complicity between all categories.

In dropping the Paco from the house name, Rabanne falls in line with a host of designer-founded brands consumers know by the family name, including Dior, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and Mugler. Albesa noted that in losing Paco, Rabanne can focus further on its feminization.

About 10 years ago, the Rabanne team presented a chart outlining how all the facets of the brand’s fashion and fragrance branches could converge, and that’s been implemented little by little since.

“From today, all that is new is completely aligned — that means we are revamping our packaging and bottles in fragrances, our strategy of how to elevate the brand,” Albesa explained. “So it’s a huge turnaround that has been cooking for years and starts to see the light now. It’s a very important elevation — keeping the values of Rabanne, for sure.”

Dossena has been key to all that in creating an overarching brand ecosystem, including what products look like, the executive underlined.

“The chemistry comes from Julien, it was his vision,” Albesa said. “Each fragrance is going to take one code of the brand, and it’s going to promote it.”

Rabanne’s perfume business, which ranks among the top-five fragrance houses worldwide, has a number of bestselling men’s scent franchises. One Million is in the top four and Invictus in the top seven. A goal for Phantom, already among the 20 bestsellers, is to climb to the top 10 by 2025.

To start shifting the scales, with women’s fragrances taking on greater weight, there’s been a change of strategy.

“We decided to work on stand-alone feminines,” said Albesa, referring to Fame, with its own advertising and vision. “We are choosing a feminine hero by brand, who will be its image. We give the feminine fragrances the capacity to shine.”

The strategy is working, with Fame becoming the best launch in 2022 in the markets where it was introduced, according to NPD Group. Further, Puig has gained a number of market share points in women’s fragrances this year and Albesa believes that momentum should accelerate.

“Then comes the makeup, which is also another way of injecting this feminization of the brand that is more consistent with the fashion,” said Albesa, who believes the time is ripe for the color cosmetics, since Rabanne has so much momentum today. “This makeup is a way to show fashion and beauty together.”

Puig has been delving into the makeup category across its stable of brands with launches for Carolina Herrera, Dries Van Noten and Christian Louboutin, not to mention Charlotte Tilbury, which the group acquired in 2020.

Taking a differentiated approach has always been key, according to Albesa. Rabanne has done that with its fragrances, coming to the market with daring storytelling and juices.

“Paco Rabanne is the first fashion designer doing indie makeup,” Albesa said. “It’s a very collective approach — by the people for the people.”

Diane Kendal was chosen to be Rabanne’s global beauty creative director. Brand executives were attracted by her philosophy that “there’s no beauty — only beauties.” Standards are not imposed.

The color cosmetics range has four categories: One for foundations, with 30 references, is dubbed Nudes. Eyephoria, for eyes, comprises 29 units; Rouge Rabanne has 21 lipsticks, while Arts Factory, with 10 skus, includes artistry-inspired products.

The gender-free products with sustainable — vegan, cruelty-free and 98 percent natural — formulas, infused with skin care, have been developed with the help of a community of people.

“It’s very modern makeup. Textures are super important,” said Albesa, calling the easy-to-use color cosmetics “nomad” due to their carry-ability.

Shimmer Bomb, with spray-on glitters, comes in an aerosol can; pressed eye powders are encased in oh-so-Rabanne metallic compacts, while foundations come in squeezy shiny tubes.

“It’s very playful makeup, which you apply with your fingers,” Albesa said.

The ad campaign — with Rabanne-clad models taking the makeup from chain-link bags, a pocket or boot, then trying it on and posing — is playful as well. Stef Mitchell photographed the ad.

The makeup’s prelaunch will take place on Rabanne’s direct-to-consumer platform rabanne.com, starting Aug. 21, followed by Selfridges on Aug. 31; Sephora in France, Italy, Germany, Spain and Portugal on Sept. 12, and Ulta at the start of October.

Prices will be in the accessible luxury range, from about $20 to $40.

Rabanne executives aim for the brand to rank among the top 10 in makeup — as well as top five in the eye segment — in doors where it is carried during launch. After, it should place among the top-15 color cosmetics brands globally by 2030.

Rabanne could ultimately stretch into other beauty categories, such as skin care.

For both Rabanne fashion and beauty, the stated purpose is to “galvanize young generations in order to forge a more inclusive and creative future.”

Albesa explained the purpose goes beyond product, to cultural relevance stretching into digital, music and communities. “We have planned for each of our brands to have a cultural aspect,” he said.

Spanish founder Paco Rabanne died last February at age 88, remembered for his futuristic vision and use of nonconventional materials.

The house went through a silent period to mourn his death, with Dossena paying homage at his fall 2023 show last March, parading some archival dresses for the finale.

(Dossena started dabbling in menswear starting with the spring 2020 season, but it was quickly phased out.)

Albesa declined to give revenue figures for the fashion house, but said year-to-date, fashion sales have been doubling.

Dossena’s designs are sold in about 300 wholesale doors. In addition to the Avenue Montaigne flagship, which opened at number 39 in 2021 and replaced a unit for Nina Ricci, also owned by Puig, there is a smaller Rabanne store on Rue Cambon.

Albesa noted the brand’s direct-to-consumer sales are tracking 80 percent ahead of last year.

The executive said he’s zeroing in on a lease for a Rabanne flagship in New York’s SoHo district that should open in the first half of 2024. After that, he has his sights set on London for the next location.

The Avenue Montaigne flagship is also slated to double in size next year.

Such developments should help counter the lingering industry perception that Barcelona-based Puig, while formidable with fragrances and beauty products, doesn’t have its heart in the fashion business.

Albesa argued that Puig is unique among Europe’s big luxury groups insofar as it operates brands, not separate fashion and beauty divisions, which can create an aesthetic gulf.

For example, when Belgian designer Van Noten launched fragrance and lipstick last year, he approached those categories just like he sets about creating his fashion, garden or home decor: with a clash of concepts and a riot of colors, prints and textures.

Albesa called it “a beautiful exercise of how the DNA of the fashion came into the beauty.”

Still, he acknowledged there is work to do in growing the d-to-c portion of Puig’s fashion houses’ sales via directly operated retail; in building lucrative accessories categories, and improving gross margins in apparel.

“We still need two, three years to fine-tune those three subjects,” he allowed. “We take it very seriously, though perhaps we work at a different speed. We don’t face the same pressure as other groups so we’ve been putting a lot of thought in what we do.”

Albesa noted that Rabanne has expanded the product range around its popular chainmail 1969 bag, including nano and micro versions, whose origins can be traced back to the steel aprons worn by French butchers back in the day.

“All of a sudden we see a lot of young consumers wanting to own a piece of Rabanne,” Albesa marveled.

Summary:

• Rabanne has been enjoying 40% growth in recent years and is expected to reach 1 billion in revenue in the very near future.

• For the past five years, Paco Rabanne has been going through a unification, elevation and "feminisation" strategy.

• This includes renaming the house as "Rabanne", a new logo, a new monogram, launching make-up and a refocus on women's fragrances.

• Julien Dossena will continue to be the creative director with his contract having been recently renewed.

• The house is also introducing eveningwear, denim and knitwear category, starting from the Spring/Summer 2024 collection.

• The Avenue Montaigne store is doubling in size, alongside the opening of a flagship store in New York in early 2024.

• There are also plans of opening a store in London.

LadyJunon

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 11, 2021

- Messages

- 3,124

- Reaction score

- 5,706

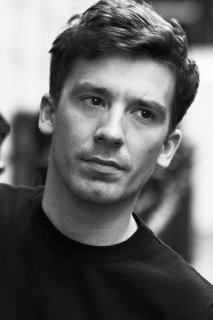

Recent interview with Harper's Bazaar. The interview discusses his early years, his career at Balenciaga, the creation of Atto, the revival of Rabanne, his collaborations with Jean-Paul Gaultier and H&M.

Interview in original language:

Director: Élodie David-Touboul

Clothing: Rabanne.

Models: Cyrielle Lalande (Ford Models), Seng Khan (Women), Marina Moioli (Premium Models), Franziska Jetzek (Women), Mary Ukech (IMG).

Hair: Jacob Kajrup.

Make-Up: Petros Petrohilos.

Manicure: Beatrice Eni.

Assistant Stylists: Pauline Charrière and Rachel Touboul.

Production: Producing Love

Source: Harper's Bazaar

Interview in original language:

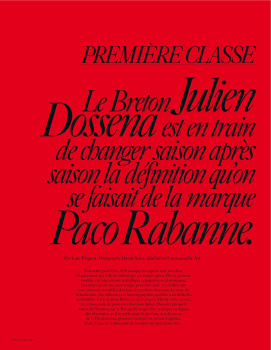

Translation:Rencontre avec Julien Dossena, directeur artistique de Rabanne

BY OLIVIER NICKLAUS

PUBLIÉ LE 19.10.23 À 13H42

Depuis dix ans, Julien Dossena ravive la flamme de Paco Rabanne, temple avant-gardiste de la mode à l’aura métal hurlant. Les deux pieds dans son époque, ce créateur aux solides convictions séduit les femmes avec des propositions réfléchies et ambitieuses. Il vient également signer la dernière collection Gaultier couture, une capsule avec H&M, et lance une ligne de maquillage sous étendard Rabanne. Suivez le garçon…

Au pied de l'immeuble parisien situé à l’angle de l’avenue Montaigne et de la rue François-Ier, la boutique Rabanne étrenne son nouveau logo. Le groupe Puig, propriétaire de la maison, a choisi de garder la même typo, mais de faire disparaître le “Paco”, à l’instar de Saint Laurent ou Mugler qui ont eux aussi perdu leurs “Yves” et “Thierry” (ou “Manfred”). À cette différence près qu’ici, le designer d’origine, Paco Rabanne, n’est mort qu’au mois de février dernier... Trois étages plus haut, Julien Dossena, à la tête de la maison depuis pile dix ans, nous accueille. Deux petites rides verticales sont creusées entre ses yeux, preuve que cet infatigable ne relâche pas ses efforts. Surtout en cette année de 10e anniversaire qui, outre le changement de logo, le voit assurer une collaboration haute couture avec la maison Jean Paul Gaultier, une autre avec le géant de la fast fashion H&M, et même le lancement d’une toute nouvelle gamme de cosmétiques. N’en jetez plus ! Mais il en faudrait plus pour tourner la tête de Julien Dossena. Il a su imposer et se faire respecter pour un travail de fond, exigeant et toujours très pensé.

Ne pas compter sur lui pour phosphorer une mode importable type veste à trois manches. Ni, à l’autre extrémité du spectre, pour des tendances de saison superficielles ou anecdotiques. Sérieusement, patiemment, il a remis à plat l’ADN de Paco Rabanne et en a gardé ce qui lui semblait pertinent pour habiller la femme d’aujourd’hui avec rigueur, modernité, et une certaine cérébralité parfois : des coupes fluides et pratiques, une gamme allant du simple T-shirt parfait, du crop top en mesh à la minijupe en assemblage de disques circulaires ou la robe maille métallique ultrasophistiquée. De saison en saison, il s’est construit une clientèle qui a commencé par des petites pièces et, avec le temps, s’est aventurée sur des spécimens plus iconiques. D’un calme olympien, il reçoit entre des bruits de perceuses et un shooting d’accessoires, et prend le temps, habillé d’un pantalon en velours de gentlemanfarmer en plein été, de revisiter un parcours déjà riche commencé à l’école de La Cambre, à Bruxelles, il y a vingt ans déjà. Un point d’étape pour un créateur qui, pour filer une métaphore sportive, en a encore largement sous le pied.

Comment est née votre vocation de designer ?

J’ai grandi en Bretagne où vit encore ma famille, dans un village de pêcheurs. Enfant, j’avais tendance à m’y ennuyer, et ma façon d’échapper à cet ennui a été le dessin. J’ai cherché naturellement un métier qui pouvait passer par cette activité. Petit à petit, vers 14-15 ans, j’ai commencé à penser à la mode : j’avais conscience que c’était un métier qui existait, qui était porté par une industrie. Ça a toujours été comme une espèce de fantasme, assez tôt, mais que je n’arrivais pas à m’autoriser. Ma famille était très éloignée de la mode. Mes parents avaient un rapport plus pragmatique que stylistique avec tout ça : ma mère montait à cheval, mon père était dans un club. J’avais juste un grand-père sculpteur et une grand-mère prof qui m’a amené à la lecture, au cinéma. Mais la mode, pour eux, c’était un peu le grand méchant capital. Et puis il y avait ce lien sous-entendu avec l’orientation sexuelle : c’était un peu comme faire mon coming out, finalement. Bref, tout cela pour expliquer que j’ai longtemps louvoyé avant d’assumer.

Quelles études avez-vous suivies ?

Je suis allé en prépa à Duperré. Venant de province, c’était la seule école d’arts appliqués dont on parlait pour le stylisme ou la mode. Après, j’ai eu envie de faire une école belge. J’avais l’impression qu’à Paris, le Graal, c’était de finir chez Dior ou Chanel et de savoir faire une chemise “jolie madame”. J’avais la sensation que ce n’était pas assez radical. Je suis allé voir les défilés de fin d’année de deux écoles, à Anvers et à Bruxelles. Ça m’a totalement chamboulé. J’ai finalement choisi La Cambre, à Bruxelles, parce qu’à Anvers j’avais peur de la barrière de la langue. J’y ai étudié cinq années, dont la dernière émaillée de stages à Paris car mon nom commençait à circuler. En 2006, j’étais encore étudiant à Bruxelles lorsque ma collection de fin d’année a remporté deux prix. Mais mon obsession, à cette époque-là, c’était de rentrer chez Balenciaga. J’ai eu d’autres propositions, mais je pensais qu’il fallait que je sois là à ce moment de mon parcours.

Qu’est-ce qui vous séduisait dans le Balenciaga proposé par Nicolas Ghesquière ?

Je me retrouvais dans toute la proposition : la modernité, le mélange de références, y compris culturelles. J’adorais la direction artistique au sens large, jusqu’aux boutiques. C’était à la fois très intellectuel, mais aussi très sensuel. Sans parler des références pop qui venaient jaillir au milieu de tout ça. Étrangement, ça ne m’intimidait pas et je me disais que je pouvais y apporter quelque chose. J’y suis resté cinq ans. Au départ j’étais stagiaire, puis j’ai eu un job de designer junior, et ainsi de suite. Et j’ai commencé à travailler avec Nicolas au bout de six-huit mois. Il m’a appris mon métier. Surtout à toujours pousser les choses, toujours être curieux, de ne jamais se satisfaire de la première lecture, d’essayer de surprendre en permanence, d’aller chercher quelque chose à un endroit où on ne l’attend pas forcément. Sa conception, c’est que pour durer, il faut toujours se renouveler et ne jamais se reposer sur ses acquis.

Après Balenciaga, en 2012, vous avez lancé Atto, votre propre maison…

Chez Balenciaga, j’étais passé en free-lance car je pensais déjà à ce projet. C’était six mois avant le départ de Nicolas Ghesquière, donc ça s’est fait comme une espèce de prédépart. Mais quand Nicolas s’en est allé, Balenciaga a viré toute son équipe, ça a été assez brutal. J’ai donc récupéré du temps pour avancer sur ce projet. Tout s’est fait dans un mouchoir de poche. Je présentais Atto en janvier. J’ai arrêté de travailler chez Balenciaga un mois avant. Toujours en janvier, Paco Rabanne est venu me chercher pour faire une mission ambulance free-lance un mois et demi avant le show de la designer précédente, Lydia Maurer. Ils avaient besoin de quelqu’un qui sorte des thèmes parce qu’ils étaient en ******. J’ai travaillé de janvier à mars, et, au mois d’avril, ils m’ont demandé si je voulais reprendre Paco Rabanne. Je me suis retrouvé d’un coup avec cette nouvelle direction artistique dans laquelle il fallait que je fasse mes preuves en plus de ce projet, Atto. Et j’ai réussi à assurer le coup pendant deux saisons. Le problème, c’est qu’Atto a marché. Donc il y avait tout de suite une grosse prod, de gros enjeux sur cette marque alors que c’était de toutes petites collections, ça devait être quarante références. Je passais mes journées chez Paco Rabanne, et mes soirées et mes nuits sur Atto. C’était l’année de mes 30 ans et je n’avais plus de vie privée, plus rien. Impossible de faire les deux. Donc j’ai lâché Atto…

Dans quel état était la maison Paco Rabanne quand ils vous ont sollicité ?

Pour être franc, c’était une maison dont personne n’attendait plus grand-chose, concernant la mode en tout cas. Pour la jeune génération qui n’avait pas connu la splendeur du couturier, Paco Rabanne leur évoquait le parfum 1 Million, et les images de ce parfum qui étaient très ancrées dans la culture populaire. C’est à peu près tout. Quand la marque a voulu relancer la mode, ils se sont dit de façon assez maligne : “Si on veut continuer à étendre et pérenniser le succès des parfums, on a besoin de fioul créatif.” Dans ma construction de designer, il y avait beaucoup de Paco Rabanne parce que dans l’histoire de la mode et du design, c’est un jalon culturellement très important. Une association de différentes valeurs esthétiques que je trouvais sublimes, une sorte de sensualité qui s’associe avec le métal, un truc très pop et un truc très intellectuel, et radical en même temps. Sur cette plateforme un peu unique, je sentais qu’il y avait un terreau particulièrement fertile pour imaginer une marque contemporaine. L’intention n’était pas de jouer sur le rétro, mais sur l’idée d’innovation, de toujours explorer. Et de toujours se relier au corps, c’est-à-dire avoir une femme dont on sent la peau, la sensualité. En tant que designer, j’étais assez excité par cet équilibre. On s’est lancé comme ça, mais le bon truc quand personne n’attend plus rien de quelque chose, c’est qu’on a une liberté totale. La proposition peut être complètement nouvelle. Personne ne va arriver en disant : “Ce n’est pas très Paco Rabanne, tout ça.” On était douze au tout début, des gens que j’ai recrutés moi-même au fur et à mesure. Il y avait un léger esprit de gang : on débarquait, on avait tous envie, on n’avait pas de limites. Ensuite, ça a beaucoup grandi, et maintenant nous sommes une centaine.

Quel rapport avez-vous eu avec Paco Rabanne lui-même pendant ces dix années ?

Je ne l’ai jamais rencontré. C’est drôle parce qu’il a grandi pas très loin de chez moi, à côté de Quimper. Et il était retourné y vivre à sa retraite. Un de ses vieux amis m’avait dit qu’il aimait ce que je faisais – j’ai apprécié le compliment – et que, si un jour, en Bretagne, je voulais le rencontrer, ce serait possible. Mais un peu en sous-main, comme ça, de lui à moi, sans passer par un truc de boulot. J’ai répondu que j’étais très touché. Mais je voulais être poli et respectueux. J’avais conscience qu’il avait créé une marque à son nom qui exprimait ses obsessions, que je la transformais, et je ne suis pas sûr qu’à sa place j’aurais eu envie de rencontrer mon successeur. Donc je ne voulais pas l’ennuyer. D’autant plus qu’il avait été très clair et radical, comme à son habitude, en disant : “La mode est derrière moi. Je ne toucherai plus jamais à rien dans le design et je ne veux plus rien avoir à faire avec cette industrie.” Il avait laissé ce chapitre derrière lui, et je n’avais pas envie d’être une sorte de grain de sable dans son quotidien.

Comment regardez-vous le chemin parcouru chez Rabanne ? De façon linéaire ou plus accidentée ?

J’ai eu la sensation d’un travail acharné, des équipes et de moi-même, en essayant de garder constamment en tête qu’on était là pour avancer, de faire en sorte que notre vision soit à chaque fois très nouvelle. On a toujours été très solidaires. Par exemple, au tout début, les gens trouvaient que c’était trop intello, un peu sec pour une histoire de sensualité. Mais on a continué sur notre lancée. On savait que c’était par cet endroit-là qu’on devait passer. On a dû aussi composer avec cette tendance qu’ont les directions de vouloir que vous refassiez ce qui a marché. Mon positionnement, c’est de dire : on va avancer, parce que la mode ça avance, et il ne faut pas qu’on refasse la même chose pendant trois saisons. Ça s’est développé par paliers, avec de grosses accélérations par moments. Je me souviens qu’avant 2020, juste avant l’épidémie de Covid, il y a eu une espèce de montée où on a vendu en une saison deux fois plus de vêtements que la saison précédente. Après, ça n’a pas cessé d’être le cas, c’est-à-dire qu’à chaque saison, on vendait deux fois plus. Et puis il y a eu la crise sanitaire qui a été un gros séisme pour tout le monde. Un moment durant lequel on était tous un peu paralysés. Et c’est vrai que l’après-Covid a été difficile parce qu’il fallait repartir avec la même vitesse et la même ampleur, tout en sortant d’une hibernation. On ne savait plus sur quel pied danser, et sur quel rythme surtout. En fait, on se rend compte que le rythme est reparti de plus belle. Je ne sais pas comment le prendre, même deux ans après. Est-ce que les questions qu’on s’est posées pendant le Covid sont obsolètes ? Ou est-ce qu’on peut faire mieux, et si oui, comment ?

Où vous êtes-vous réfugié pendant la crise du Covid ? Êtes-vous resté à Paris ?

Je suis parti à la campagne, pas très loin de Paris, avec deux amis. On est resté là pendant trois mois. Ce qui est terrible, c’est que c’était super. Je n’avais pas envie que ça se termine, et j’avais même peur de revenir en ville. C’était comme un retour en enfance, bizarrement. Ça faisait des années que je n’avais plus le souvenir d’avoir pu voir le printemps : les arbres qui se couvrent de feuilles, les fleurs, les oiseaux, toutes ces sensations qu’on n’a plus depuis longtemps. J’ai eu une sorte de mini-angoisse en revenant. Qu’est-ce que tu fais maintenant ? Des robes ? OK, mais qu’est-ce que tu veux dire de ça ? Qu’est-ce que tu as envie de dire ? Un questionnement qui a duré un peu, quand même. Ce n’est pas que je ne savais plus quoi dire, mais c’était un peu plus laborieux.

Parmi les nombreuses actus, il y a votre collection Gaultier haute couture de juillet dernier…

J’étais comme un gamin ! Je me souviens d’avoir vu, enfant, Gaultier à la télévision, et de me dire que ça avait l’air incroyable. Il était entouré de gens fous, comme une bande qui s’amuse, qui propose des nouvelles choses, qui exprime des personnages, des cultures et des mélanges que je n’avais jamais vus comme ça. On sentait qu’à chaque fois il ramenait ce qu’il avait observé. Pour les rabbins, il était allé chiner dans le quartier juif de Londres et avait vu tous ces rabbins sortir en procession, et s’était dit “waouh, ils sont d’une élégance incroyable”. C’est comme si on se mettait avec lui à la terrasse d’un café. Je trouvais ça très beau, cette générosité et cet amour des gens qu’il observait. Il retranscrivait ça comme un sociologue poétique. Cette proposition très pop, très généreuse, a fait partie de mon éducation d’adolescent. Plus tard, j’ai découvert la sophistication incroyable de sa mode. C’est une sorte de néocouturier, de néoclassique. Quand ils m’ont proposé de faire cette collection, j’ai immédiatement accepté avec une grande jubilation. Lorsque j’ai démarré, Haider Ackermann réalisait la collection précédente, en janvier, et je trépignais un peu : je savais que j’allais avoir accès aux équipes, aux ateliers. Je commençais déjà à réfléchir. Je l’ai pris comme une espèce de déclaration : c’était très important pour moi que ça puisse toucher Jean Paul. Au fond, c’est un peu le même travail que j’ai fait chez Paco Rabanne, mais d’une façon encore plus proche. J’ai rencontré Jean Paul, on a déjeuné ensemble à plusieurs reprises. Je l’ai vraiment fait pour lui. Il y avait un bonheur. J’ai retrouvé dans mon métier cette joie de l’accomplir tous les jours, j’allais à pied avec mon sac à dos rue Saint-Martin, dans le Marais. Les équipes sont incroyables. Le fait de travailler avec ses ateliers qui ont été formés par lui, qui n’ont pas de limites créatives, qui ont une sensibilité très particulière, qui est la sienne au départ, et cette expertise dans leur domaine et dans leur métier. C’était réellement très inspirant. C’est comme si ça m’avait reboosté pour plusieurs années.

Il y a eu aussi la collaboration avec H&M qui correspond à la volonté de Rabanne de s’ouvrir à un public plus large…

Au tout début, j’étais assez circonspect. Ils ont proposé qu’on se rencontre et je me suis rendu compte qu’ils offraient une énorme liberté, et qu’ils donnaient des moyens. Leurs équipes sont performantes. Pour moi, le premier principe, c’était la recherche de sustainability [durabilité] maximale. Ils s’y sont tenus. Ils ont même développé de nouvelles choses qui n’existaient pas, comme de la maille métallique recyclée et recyclable. Évidemment, je n’avais pas du tout envie de faire une version cheap de mon design et je dois dire que la qualité de réalisation est impeccable. Pour attraper une dimension en effet plus mainstream de Paco Rabanne, on a aussi fait des objets pour la maison : des tabourets, des lampes. Pour la communication, j’ai pu travailler avec des photographes et des réalisateurs avec qui j’avais toujours eu envie d’exercer. C’est donc plus mainstream, mais sans jamais rien céder sur le niveau de sophistication. C’était à l’autre bout du spectre de la couture avec Gaultier, mais extrêmement intéressant aussi. Et puis, ça range les choses. En faisant ça, on rend notre design accessible. Chez Rabanne, on reste sur le cœur de la création et ses déclinaisons, mais en limitant quand même l’ouverture. Ainsi, on me demande régulièrement une doudoune – que je refuse toujours de faire pour l’instant !

Que pensez-vous de la nomination de Pharrell Williams chez Louis Vuitton ?

C’est intéressant, car c’est l’évolution de l’industrie. Ça raconte qu’aujourd’hui ce métier peut être exercé par des créatifs venant d’autres champs. Ça suggère qu’on n’a plus forcément besoin de la formation et de l’expérience, comme ce que j’ai pu connaître. Il n’y a plus le couturier dans sa maison qui porte son nom et qui exprime son univers. On sentait déjà ça avant les réseaux sociaux et la nomination de Pharrell chez Vuitton. Aujourd’hui, les compagnies sont beaucoup plus grosses, des structures qui ont des aspects qu’on n’imaginait pas il y a encore quinze ans. Je ne suis pas hostile à l’idée d’explorer plusieurs champs en même temps. Je ne ferai jamais d’album musical, mais je créerai peut-être autre chose ailleurs. Je ne veux pas être dans le regret ou la tristesse. Ce changement du métier comporte aussi des chances.

Que faites-vous lorsque vous ne travaillez pas ?

Je lis pas mal, surtout le soir. Le week-end, je ne suis pas souvent à Paris. J’ai une maison à la campagne, à moins d’une heure de voiture, que j’ai achetée l’hiver précédant l’épidémie de Covid et que j’ai entièrement retapée. J’y vais dès que je peux. Ma vie sociale est donc plus concentrée sur Paris la semaine.

Qu’aimez-vous le plus dans votre métier ? Et le moins ?

Le plus, c’est de pouvoir explorer, d’avoir la chance de s’exprimer régulièrement, de rencontrer souvent de nouvelles personnes, ce sont les équipes. Le moins, c’est ce rythme imposé où on doit être inspiré tout le temps, et où le temps de création est de plus en plus court. Parfois, j’ai le sentiment de ne pas avoir eu le temps d’aller jusqu’au bout d’une idée. Frustration donc, et pression aussi, car c’est une industrie très compétitive.

Photoshoot:Meeting with Julien Dossena, artistic director of Rabanne

BY OLIVIER NICKLAUS

PUBLISHED ON 10/19/23 AT 1:42 p.m.

For ten years, Julien Dossena has rekindled the flame of Paco Rabanne, an avant-garde temple of fashion with a screaming metal aura. With both feet in his time, this creator with solid convictions seduces women with thoughtful and ambitious proposals. He also signed the latest Gaultier couture collection, a capsule with H&M, and launched a makeup line under the Rabanne banner. Follow the boy...

At the foot of the Parisian building located at the corner of avenue Montaigne and rue François-Ier, the Rabanne boutique is launching its new logo. The Puig group, owner of the house, chose to keep the same typography, but to remove the “Paco”, like Saint Laurent or Mugler who also lost their “Yves” and “Thierry” (or “Manfred”). Except that here, the original designer, Paco Rabanne, only died last February... Three floors higher, Julien Dossena, at the head of the house for exactly ten years, welcomes us. Two small vertical wrinkles are dug between his eyes, proof that this tireless person does not let up his efforts. Especially in this 10th anniversary year which, in addition to the change of logo, sees him ensure a haute couture collaboration with the house of Jean Paul Gaultier, another with the fast fashion giant H&M, and even the launch of a whole new range of cosmetics. Don't throw any more away! But it would take more to turn Julien Dossena's head. He knew how to impose and be respected for his in-depth, demanding and always well-thought-out work.

Don't count on it to phosphorize an wearable fashion such as a three-sleeve jacket. Nor, at the other end of the spectrum, for superficial or anecdotal seasonal trends. Seriously, patiently, he reassessed the DNA of Paco Rabanne and kept what seemed relevant to him to dress today's woman with rigour, modernity, and a certain intellect sometimes: fluid and practical cuts, a range ranging from the perfect simple T-shirt, from the mesh crop top to the mini skirt made from circular discs or the ultra-sophisticated metallic mesh dress. From season to season, he built a clientele that began with small pieces and, over time, ventured into more iconic specimens. With Olympian calm, he receives between the sounds of drills and an accessories shoot, and takes the time, dressed in gentlemanfarmer's velvet pants in the middle of summer, to revisit an already rich journey begun at the school of La Cambre, in Brussels, twenty years ago already. A milestone for a creator who, to use a sporting metaphor, still has a lot under his belt.

How was your vocation as a designer born?

I grew up in Brittany where my family still lives, in a fishing village. As a child, I tended to get bored there, and my way of escaping this boredom was drawing. I naturally looked for a job that could involve this activity. Little by little, around 14-15 years old, I started to think about fashion: I was aware that it was a profession that existed, that was supported by an industry. It was always like a kind of fantasy, quite early on, but one that I couldn't allow myself to have. My family was very far from fashion. My parents had a more pragmatic than stylistic relationship with all this: my mother rode horses, my father was in a club. I just had a grandfather who was a sculptor and a grandmother who was a teacher who took me to reading and to the cinema. But fashion, for them, was a bit like the big bad capital. And then there was this implied link with sexual orientation: it was a bit like coming out, finally. In short, all this to explain that I hesitated for a long time before taking responsibility.

What studies did you follow?

I went to prep school in Duperré. Coming from the provinces, it was the only applied arts school that anyone talked about for styling or fashion. Afterwards, I wanted to go to a Belgian school. I had the impression that in Paris, the Holy Grail was to end up at Dior or Chanel and to know how to make a “pretty madame” shirt. I had the feeling that it wasn't radical enough. I went to see the end of year parades of two schools, in Antwerp and Brussels. It totally shocked me. I finally chose La Cambre, in Brussels, because in Antwerp I was afraid of the language barrier. I studied there for five years, the last of which included internships in Paris because my name was starting to get around. In 2006, I was still a student in Brussels when my end-of-year collection won two prizes. But my obsession at that time was to join Balenciaga. I had other offers, but I thought I had to be there at this point in my journey.

What appealed to you about the Balenciaga proposed by Nicolas Ghesquiere?

I found myself in the whole proposition: the modernity, the mixture of references, including cultural ones. I loved the artistic direction in the broad sense, right down to the boutiques. It was both very intellectual, but also very sensual. Not to mention the pop references that came bursting out in the middle of it all. Strangely, it didn't intimidate me and I told myself that I could contribute something. I stayed there for five years. Initially I was an intern, then I had a job as a junior designer, and so on. And I started working with Nicolas after six-eight months. He taught me my trade. Above all, always push things, always be curious, never be satisfied with the first reading, try to constantly surprise, look for something in a place where you don't necessarily expect it. His idea is that to last, you must always renew yourself and never rest on what you have acquired.

After Balenciaga, in 2012, you launched Atto, your own house…

At Balenciaga, I went freelance because I was already thinking about this project. It was six months before the departure of Nicolas Ghesquière, so it was like a kind of pre-departure. But when Nicolas left, Balenciaga fired his entire team, it was quite brutal. So I found some time to move forward on this project. Everything was done in a pocket handkerchief. I presented Atto in January. I stopped working at Balenciaga a month prior. Also in January, Paco Rabanne came to pick me up to do a freelance ambulance mission a month and a half before the show of the previous designer, Lydia Maurer. They needed someone to come up with themes because they were late. I worked from January to March, and in April they asked me if I wanted to take over Paco Rabanne. I suddenly found myself with this new artistic direction in which I had to prove myself in addition to this project, Atto. And I managed to keep it up for two seasons. The problem is, Atto worked. So there was immediately a big production, big stakes for this brand even though they were very small collections, there must have been forty references. I spent my days at Paco Rabanne, and my evenings and nights at Atto. It was the year I turned 30 and I no longer had a private life, nothing. Impossible to do both. So I let go of Atto…

What state was the Paco Rabanne house in when they asked you?

To be frank, it was a house from which no one expected much, at least regarding fashion. For the younger generation who had not known the splendour of the designer, Paco Rabanne evoked the perfume 1 Million, and the images of this perfume which were very anchored in popular culture. That is just about everything. When the brand wanted to relaunch fashion, they said quite cleverly: “If we want to continue to expand and sustain the success of perfumes, we need creative fuel.” In my construction as a designer, there were a lot of Paco Rabanne because in the history of fashion and design, it is a culturally very important milestone. An association of different aesthetic values that I found sublime, a kind of sensuality that is associated with metal, something very pop and something very intellectual, and radical at the same time. On this somewhat unique platform, I felt that there was particularly fertile ground for imagining a contemporary brand. The intention was not to play on retro, but on the idea of innovation, of always exploring. And to always connect with the body, that is to say, have a woman whose skin and sensuality we feel. As a designer, I was quite excited by this balance. We started like that, but the good thing when no one expects anything from something anymore is that we have total freedom. The proposal may be completely new. No one is going to come in and say: “That’s not very Paco Rabanne, all that.” There were twelve of us at the very beginning, people I recruited myself over time. There was a slight gang spirit: we showed up, we all wanted to, we had no limits. Then it grew a lot, and now there are around a hundred of us.

What relationship did you have with Paco Rabanne himself during these ten years?

I have never met him. It’s funny because he grew up not very far from me, near Quimper. And he returned to live there when he retired. One of his old friends told me that he liked what I did – I appreciated the compliment – and that, if one day, in Brittany, I wanted to meet him, it would be possible. But a little secretly, like that, from him to me, without going through any work stuff. I replied that I was very touched. But I wanted to be polite and respectful. I was aware that he had created a brand in his name which expressed his obsessions, that I was transforming her, and I'm not sure that in her place I would have wanted to meet my successor. So I didn't want to bother him. Especially since he had been very clear and radical, as usual, by saying: “Fashion is behind me. I will never do anything in design again and I want nothing to do with this industry.” He had left this chapter behind him, and I didn't want to be a sort of grain of sand in his daily life.

How do you view the progress made at Rabanne? In a linear or more uneven way?

I had the feeling of hard work, from the teams and from myself, trying to constantly keep in mind that we were here to move forward, to ensure that our vision was very new each time. We have always been very supportive. For example, at the very beginning, people thought it was too intellectual, a little dry for a story about sensuality. But we continued our momentum. We knew that this was the place we had to go through. We also had to deal with this tendency for management to want you to redo what worked. My position is to say: we are going to move forward, because fashion is moving forward, and we must not do the same thing for three seasons. It developed in stages, with big accelerations at times. I remember that before 2020, just before the Covid epidemic, there was a kind of surge where we sold twice as many clothes in one season as the previous season. Afterwards, it continued to be the case, that is to say that each season, we sold twice as much. And then there was the health crisis which was a big earthquake for everyone. A moment during which we were all a little paralyzed. And it’s true that post-Covid was difficult because we had to start again with the same speed and the same scale, while coming out of hibernation. We no longer knew which way to dance, and especially to what rhythm. In fact, we realise that the rhythm has picked up again. I don't know how to take it, even two years later. Are the questions we asked ourselves during Covid obsolete? Or can we do better, and if so, how?

Where did you take refuge during the Covid crisis? Did you stay in Paris?

I went to the countryside, not very far from Paris, with two friends. We stayed there for three months. The terrible thing is that it was great. I didn't want it to end, and I was even afraid to come back to town. It was like going back to childhood, strangely. It's been years since I remember being able to see spring: the trees covered in leaves, the flowers, the birds, all these sensations that we haven't had for a long time. I had a sort of mini-anxiety when I came back. What are you doing now ? Dresses ? OK, but what do you mean about that? What do you want to say? A questioning that lasted a little, all the same. It's not that I didn't know what to say anymore, but it was a little more laborious.

Among all the news, there is your Gaultier haute couture collection from last July…

I was like a kid! I remember seeing Gaultier on television as a child and thinking that it looked incredible. He was surrounded by crazy people, like a group having fun, offering new things, expressing characters, cultures and mixtures that I had never seen like that. We felt that each time he brought back what he had observed. For the rabbis, he went antiquing in the Jewish quarter of London and saw all these rabbis coming out in procession, and said to himself “wow, they are incredibly elegant”. It’s like sitting with him on the terrace of a café. I found it very beautiful, this generosity and this love of the people he observed. He transcribed it like a poetic sociologist. This very pop, very generous proposal was part of my adolescent education. Later, I discovered the incredible sophistication of his fashion. It’s a kind of neo-couture, neoclassical. When they asked me to do this collection, I immediately accepted with great jubilation. When I started, Haider Ackermann was producing the previous collection, in January, and I was a little nervous: I knew that I was going to have access to the teams, to the workshops. I was already starting to think. I took it as a kind of declaration: it was very important for me that it could touch Jean Paul. Basically, it’s a bit of the same work that I did at Paco Rabanne, but in an even closer way. I met Jean Paul, we had lunch together several times. I really did it for him. There was happiness. I found in my job this joy of accomplishing it every day, I went on foot with my backpack to rue Saint-Martin, in the Marais. The teams are incredible. The fact of working with his workshops which were trained by him, which have no creative limits, which have a very particular sensitivity, which is his at the start, and this expertise in their field and in their profession. It was really very inspiring. It’s as if it had reenergized me for several years.

There was also the collaboration with H&M which corresponds to Rabanne's desire to open up to a wider audience...

At the very beginning, I was quite cautious. They suggested that we meet and I realised that they were offering enormous freedom, and that they were providing resources. Their teams are efficient. For me, the first principle was the search for maximum sustainability. They stuck to it. They even developed new things that didn’t exist, like recycled and recyclable metal mesh. Obviously, I didn't want to make a cheap version of my design at all and I must say that the quality of the design is impeccable. To capture a more mainstream dimension of Paco Rabanne, we also made objects for the home: stools, lamps. For communication, I was able to work with photographers and directors with whom I had always wanted to work. It’s therefore more mainstream, but without ever giving up anything on the level of sophistication. It was on the other end of the couture spectrum with Gaultier, but extremely interesting too. And then it puts things away. By doing this, we make our design accessible. At Rabanne, we stay on the heart of creation and its variations, but still limit the openness. So, I am regularly asked for a down jacket – which I still refuse to wear for the moment!

What do you think of the appointment of Pharrell Williams at Louis Vuitton?

It’s interesting, because it’s the evolution of the industry. It says that today this profession can be exercised by creative people from other fields. This suggests that we no longer necessarily need training and experience, like what I experienced. There is no longer the designer in his house who bears his name and who expresses his universe. We already felt that before social networks and the appointment of Pharrell at Vuitton. Today, companies are much bigger, structures that have aspects that were not imagined even fifteen years ago. I am not hostile to the idea of exploring several fields at the same time. I'll never make a music album, but maybe I'll create something else somewhere else. I don't want to be in regret or sadness. This change in profession also brings opportunities.

What do you do when you're not working?

I read quite a bit, especially in the evening. On weekends, I am not often in Paris. I have a house in the countryside, less than an hour's drive away, which I bought the winter before the Covid epidemic and which I completely renovated. I go there as often as I can. My social life is therefore more focused on Paris during the week.

What do you like most about your job? And the least?

The best part is being able to explore, having the chance to express yourself regularly, often meeting new people, these are the teams. The least is this imposed rhythm where we must be inspired all the time, and where the creation time is shorter and shorter. Sometimes I feel like I haven't had time to follow through on an idea. Frustration therefore, and pressure too, because it is a very competitive industry.

Director: Élodie David-Touboul

Clothing: Rabanne.

Models: Cyrielle Lalande (Ford Models), Seng Khan (Women), Marina Moioli (Premium Models), Franziska Jetzek (Women), Mary Ukech (IMG).

Hair: Jacob Kajrup.

Make-Up: Petros Petrohilos.

Manicure: Beatrice Eni.

Assistant Stylists: Pauline Charrière and Rachel Touboul.

Production: Producing Love

Source: Harper's Bazaar

Ugh his clothes are fine and all, but his work doesn’t have any soul or heartbeat. He is one of those designers that just seems to chase a “cool girl” look. I suppose that’s valid, but I personally don’t see the appeal or the hype.

LadyJunon

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 11, 2021

- Messages

- 3,124

- Reaction score

- 5,706

Puig, the owner of Carolina Herrera and Dries Van Noten, Jean Paul Gaultier, Nina Ricci and Rabanne, has made moves to go public while retaining a majority share. The IPO could give Puig a market value of at least €13.7 billion.

Crossposted in: Dries Van Noten - Designer, Harris Reed - Designer, Creative Director of Nina Ricci and Julien Dossena - Designer, Creative Director of Rabanne

Puig Aims to Raise €2.5 Billion in IPO

The family-owned premium beauty conglomerate has confirmed it will float shares on the Spanish stock exchange while retaining majority control, following months of speculation.

By DANIELA MOROSINI

08 April 2024

Puig, the family-owned Spanish beauty conglomerate, announced plans for an initial public offering on the stock exchanges in Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao and Valencia. The company owns 14 brands including Charlotte Tilbury, Paco Rabanne and Byredo, as well as a number of fragrance licences.

The company hopes to raise €1.25 billion ($1.3 billion) through the first round of IPO, followed by a larger secondary sale that would bring the total fundraising north of €2.5 billion. The Puig family will retain a majority stake in the company and the “vast” majority of voting rights, the company said.

In 2023, Puig reported net revenues of €4.3 billion ($4.6 billion), up 19 percent, while net profit rose to €465 million ($503 million), up 16 percent on the previous year.

In October 2023, chairman Marc Puig confirmed the group was mulling an IPO among other strategic options to raise fresh capital. In a statement released today, Marc Puig said the decision was a “decisive step” in the company’s 110-year history, and that it was important to ensure the “right checks and balances” were in place during a “generational transition.”

“We believe that the balance of being a family-owned company that is also subject to market accountability will allow us to better compete in the international beauty market during the next phase of the company’s development,” said Marc Puig, adding that being a publicly listed company will align its corporate structure with those of best-in-class, family-owned companies in the global premium beauty sector. Top industry players such as L’Oréal and Estée Lauder have long been publicly traded, as well as retaining founding family ownership stakes.

The company plans to further diversify into skincare and makeup, and focus on prioritising brands it owns outright rather than licences, which can be expensive to renew and disruptive when they lapse. 95 percent of revenues came from fully-owned or majority-owned brands like Paco Rabanne, Dries Van Noten or Nina Ricci last year, Puig said.

The company has been making more acquisitions of late – in January, it purchased luxury skincare brand Dr. Barbara Sturm, following its acquisitions of Byredo and Charlotte Tilbury since 2020.

“Our unique and creative DNA has allowed us to attract leading founders and brands… We strongly believe that building premium brands requires long-term thinking,” Marc Puig said.

Currently, fragrance is Puig’s largest revenue driver. But the group’s smallest segment, skincare, grew the most in 2023, with revenues up 31 percent to €431 million ($466 million). The company has long been profitable, Puig added.

Why Puig’s IPO Timing Couldn’t Be Better